Social Work Scotland is the professional body for social work leaders, working closely with our partners to shape policy and practice, and improve the quality and experience of social services. We are a key partner in the national Adult Social Care Reform Programme, creating an operational framework for Self-directed Support across Scotland supporting consistent delivery of social care that is personalised, rights-based and which supports active citizenship. Another of our current projects is aligned to a Scottish Government programme (Health and Justice Collaboration Board) to test and implement frameworks for the delivery of integrated adult social services in Scottish prisons.

Notwithstanding ongoing progress in the national reform programme, the Health and Sport Committee’s inquiry into the future needs and delivery requirements for social care for adults is a welcome focus on the sustainability of models of social care and the investment required to support the wellbeing of Scotland’s citizens.

THE FUTURE DELIVERY OF SOCIAL CARE IN SCOTLAND

OVERARCHING THEMES

Social care is a concept that implies the delivery of a service to an individual to meet professionally defined social and health deficits. In recent years, social care has become professionalised to such an extent that it can feel institutional in nature to those receiving social care and those delivering it.

Social Work Scotland sees the role of social work downplayed in recent decades with a focus on transactional care management and adherence to bureaucratic processes and procedures. The role of social work[1] (as distinct from social care[2]) is by its nature dynamic and complex as it follows people and families through often chaotic life challenges and transitions, helping people to find the right way forward for them, enabling them to take risks, with all the attendant conflicts that this implies, and when necessary and proportionate, using statutory measures to intervene to protect people. In order for social care to be delivered to the right people in the right way, social work practice needs to be strong and delivered across the range of settings including home, hospital, residential home, care home, homelessness and prison for all vulnerable people at any age.

The social care model in Scotland was not designed or funded to meet the current expectation of provision or demand. Social Work Scotland members increasingly experience the effect that real-term spending reductions is having on their ability to sustain levels of service, maintain quality and provide non-statutory early help to prevent escalation into crisis. Social services (social work and social care) as a whole system within the integration environment with health must be sufficiently funded to meet its statutory duties.

Social Work Scotland believes that the system could be reimagined to be a much more dynamic interplay of social infrastructure supporting citizens as individuals and within families and communities, with a combined workforce operating at community level.

The Adult Social Care Reform programme, of which Social Work Scotland is an enthusiastic national partner, states that “social care support is about supporting people to live independently, be active citizens, participate and contribute to our society, and maintain their dignity and human rights”[3] Whilst there is widespread agreement with this aim, the question remains: what will it take to implement the change necessary to meet these aims for everyone in all areas of Scotland?

The reform programme takes us back to the drawing board to consider these priorities:

- “a shared agreement on the purpose of adult social care support, with a focus on human rights

- social care support that is centred on a person, how they want to live their life, and what is important to them – including the freedom to move to a different area of Scotland

- changing attitudes towards social care support, so that it is seen as an investment in Scotland’s people, society and economy

- investment in social care support, and how it is paid for in the future

- a valued and skilled workforce

- strengthening the quality and consistency of co-production at local and national level with people with lived experience and the wider community

- equity of experience and expectations across Scotland

- evaluation, data and learning”

It is critical that we understand the essential elements that contribute to successful implementation of whole-system change: the person’s life journey both within and outwith the system, what matters to the person and their families and what they need to be fully in control of their life, regardless of their disability (visible or hidden) or health condition, which social work and social care policies and practices are useful and how we can ensure that they are reliably delivered by a well-trained and supported workforce, what the infrastructure needs to look like (including community assets, accessible housing, case management IT systems, technology, administrative support, commissioning and procurement, eligibility policy, finance and budgeting systems), and the qualities, skills and behaviours of adaptive systems leadership.

Adult social work and social care contributes to the wider system of integrated social and health care and support, which in turn, we believe, should be better embedded within local community planning processes.

- How should the public be involved in planning their own and their community’s social care services?

Social Work Scotland supports the approach of active citizenship, where people are involved at all levels of decision-making and throughout strategic and individual planning and commissioning processes. We recognise that community engagement requires considerable time and workforce resource to be done well.

Through representation on their Integration Joint Board, many communities may have already expressed their views of local social care needs but this does not necessarily reflect in the services commissioned by Health and Social Care Partnerships.

Participatory budgeting and the allocation of small community investment funds have helped develop some good preventative community-based social care activities across Scotland[4] (such as dementia cafés and Men’s Sheds) but are generally funded only for one year and heavily rely on volunteers. While helping to address identified community social care needs, such initiatives are often not sustainable.

We welcome the development of new community engagement guidance for integration authorities under the Integration Review. However, over the past decade, support to build community capacity, in the shape of community learning and development services, community workers, and grants to community groups, has been critically reduced across Scotland. Investment is required to ensure that communities are ready and resourced to engage in strategic planning and commissioning processes. Independent support organisations, such as those funded by Support in the Right Direction (SiRD), are vital in ensuring the voice of people who use services and carers are invited and heard.

True engagement needs to start where people are at, so local partnerships need to be imaginative and creative about seeking views from people, in ongoing and multiple ways. Engagement should lie at the heart of decision-making and is the key to people having meaningful choice and control in their own support. Engagement therefore supports the principles of personalisation underpinning Scotland’s Self-directed Support (SDS) legislation. Practically, good engagement that personalises social care means that care arrangements are more likely to meet needs and less likely to go wrong.

There already exists a range of asset-based resources and approaches to support people to engage. The National Involvement Network’s (2015) Charter for Involvement “sets out in their own words how supported people want to be involved, in the support that they get, in the organisations that provide their services, in the wider community”[5].Supported Decision Making[6] can help some people’s views and choices to be expressed. The Care Programme Approach[7] is designed to provide a wider structure of care and support to people with mental health problems. The Good Conversations approach[8] engages with people about their personal outcomes.

However, these resources are used in a piecemeal way across Scotland, and are largely abandoned when budgets are tight. In order to implement these approaches, which often conflict with the traditional ‘way we do things’, attention needs to be given to workforce training and coaching, supportive systems and devolved leadership.

We feel very strongly that there needs to be consideration of the range of people’s lived experience when designing and constructing social work and social care services. Often the focus of social care is older people with personal care needs due to frailty or long-term conditions and people with physical disabilities, with other experiences not well supported including mental illness, learning disabilities, alcohol and drug addiction, domestic abuse, families at the edge of care, care-experienced children and young people, people vulnerable to abuse and those in our justice system, who tend to come from communities experiencing the greatest health and social deprivation. It would be helpful if the Health and Sport Committee could take cognisance of the review of mental health legislation in Scotland where Social Work Scotland will be making similar points regarding the need for early intervention, better resourcing of community supports, and greater choice and control.

As SDS helps move choice and control to the individual and as communities take on more social care support though community empowerment, we wonder if some of the obligations of regulation need also to move to the individual or community, and the role of regulatory and inspection bodies reconsidered.

- How should integration authorities commission and procure social care to ensure it is person-centred

Social work and social care financing needs to be sufficient to support the quantity and types/models of care necessary to support our population. Services in many areas of Scotland are currently constrained such that they are only able to address substantial and critical risks (as defined in the National Eligibility Criteria[9]) by the provision of personal care only, leading vulnerable people to struggle when their needs change or when their needs are social in nature rather than physical.

Scotland should embrace a human rights based approach to care. Underpinning principles should cover the range of activities necessary for active citizenship, including reducing isolation, supporting people to make and maintain friendships, promoting vocational skills, supporting people to develop and enhance life skills, promoting physical and mental well-being, and mitigating health inequalities.

This would involve supporting people with complex needs in personalised ways, supporting carers, promoting SDS and personalisation within partnerships, working with people at the earliest opportunity to maintain, improve or maximise independence, building capacity in the community and with sustainable services, ensuring best value and effective partnership working, reducing dependence on high-tariff services, and creating services that are aware and confident about using and utilising technology.

Social Work Scotland recognises the progress being made by integration authorities in strategic commissioning, though it is notable that current commissioning practices are not well placed to support personalised options. Audit Scotland[10]found that SDS Option 2 in particular is not fully developed.

SDS legislation calls for innovative solutions to allow people to hold individual service funds, necessitating a shift in commissioning practice from block funding to personal commissioning, to enable more freedom of choice and greater control. The Care Inspectorate[11] did find that local authority finance teams were becoming more knowledgeable, less risk-averse and more open to creative use of personal budgets, though this is by no means wide-spread.

Most services commissioned and arranged by the local authority (Option 3) are delivered on the basis of ‘time-and-task’, and this is runs counter to a human rights-based approach to delivering care and support, because people’s needs and choices naturally change on a day-to-day basis. Introducing more of a personal approach to is essential to assist people receiving supports in a way that meets their personal outcomes. We believe that quantifying ‘time’ rather than ‘task’ would allow greater choice and control by individuals, whilst allowing for a budget to be allocated.

We echo COSLA’s view that the lack of variety in the social care market is contributing to rigidity and lack of choice, and think that addressing this should be a priority. Social Work Scotland is aware of innovation in commissioning such as alliance contracting, which could be explored.

In future, integration should give rise to the pooling of health and social care budgets to form personalised care packages controlled by the person.

- Looking ahead, what are the essential elements in an ideal model of social care (e.g. workforce, technology, housing etc.)?

We shouldn’t be thinking about an ideal model of social care; an ideal is neither possible nor desirable. Scotland is a country with significant geographically and economically variation, with a diverse and vibrant citizenship with whom we should be aiming to personalise care and support and to offer people choice and control of how they want to manage their lives.

The promise of integration has not yet been realised, though a major shift in professional structures and organisational dynamics could not feasibly happen in a few short years. In some settings where social care and support is required, other partners need to be more fully involved such as the Scottish Prison Service in regards to prisons and local authority housing departments who are key enablers in providing environments to meet the needs of their populations.

We do think that there are essential elements that can support a revitalised and redesigned system of social work and social care but we fear that implementing integration and reforming adult social care by attempting ambitious systemic change without methodological rigour will fail.

We recommend that the committee considers what implementation science might offer in our national attempts to implement complex social policies consistently across Scotland. We believe that this approach is the most suited to undertaking the sort of complex, adaptive change required to meet Scotland’s ambitious progressive policies. Scotland hosts national expertise in the form of the Active Implementation approach supported by the Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland (CELCIS)[12], University of Strathclyde. Social Work Scotland is commissioning CELCIS to support its project work, including the national SDS and Social Care in Prisons projects.

Self-directed Support

As noted in the introduction, Social Work Scotland is hosting the national Self-directed Support project on behalf of the Scottish Government and COSLA. Learning from past experience, we are committed to understanding what it will take to embed SDS in a sustainable manner across the geographies of Scotland and across all care groups equally. In accordance with best international implementation practice, this includes examining practices and tools for their effectiveness and fidelity, and understanding and promoting the system drivers necessary for adaptive change.

This project is in its early stages, but essential components will include community infrastructure and assets, help to galvanise natural family and community supports, personalised assessment and support planning, resource release models, and review processes.

The underpinning questions is what are the essential elements for a good life as an active citizen in all environments. This includes respecting human rights, having loving relationships, a decent income, the opportunity to learn, work and contribute, to be part of a community, to have a home that can adapt to your needs, support to maintain health and wellbeing and when you need support to be able to have a say in how, when and what that support looks like.

This entails a well-trained and adequately paid workforce, access to transport and technology and to feel safe where you live. Personalisation and Self-directed Support are at the heart of good social work and good social care, and should be the key driver in local planning processes.

Building assets

Current application of the National Eligibility Criteria presumes that intervention for anything less than critical and substantial risk can be picked up by family or local community and that the person has the capacity to organise and manage sometimes complex arrangements. In some settings (for example prison) people do not have this level of family or community support and are not able to follow signposting to where third sector support might be available. Lack of early help precipitates crises which are costly in outcomes for the person and financially for the local authority.

A radical shift of focus of integration authorities to support people to self-manage, on personalising care and support at home and on effective early intervention and prevention would involve working collaboratively with a wider range of partners including education, housing and community representatives using shared decision-making processes and sharing both risk and responsibility. The current approach to eligibility is impacting too severely on vulnerable people and those at the edge of social care, and we recommend that the National Eligibility Criteria are reformed.

An early intervention approach would see social workers move away from care management to working relationally and enhancing the natural supports of family, friends and neighbour’s contribution through such models as Family Group Decision Making. However, as the working age population is set to shrink while the older population will increase as the baby-boomer generations reach older age, this population shift will impact disproportionately on women, who provide most of the – care to family members. Consideration must be given as to how Scotland can best support carers.

Where localities are well-resourced and organised, consideration could be given to devolving budgets to enable integrated teams to develop local services and supports. Health and Social Care Partnerships approach to locality working could have, as the norm, integrated teams (community social work and community nursing) who hold their own budget and involve community representatives and local providers in regular place-based conversations. Alternative models already being tested in Scotland include Buurtzorg in the form of Neighbourhood Care[13] approach and Community-Led Support[14]. There have been attempts made to revitalise a Community Social Work[15] approach in some areas.

Under existing SDS legislation individual budgets can be provided to people to procure their own service and support where they are comfortable and supported to do so, although this happens infrequently.

It is of critical importance to develop a strong Third Sector with investments from Government to ensure partnership and sustainability. There should be a consideration to supporting local partnerships to commission more specialist services (those that are high cost and risk, but low volume) on a regional or national basis.

Housing

Houses should be designed for people to live in through life into older age and for those with increased dependency. This would include the ability to retrofit hoists and large equipment and should have technology built-in. Such housing should be affordable and be sited at the heart of the community.

There are tensions and barriers to more productive working with housing developers, largely due to the planning system and financial pressures on housing associations which prevent ambitions around accessible housing – for older people and housing for life – to be built. The best practice guidance issued by the Scottish Government for more accessible housing is not a requirement and has proved challenging to comply with, and we think there is merit in examining industry standards for accessibility to consider whether they are fit for purpose. There are some very positive examples of best practices driven by the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations such as technological solutions in housing[16], but these are limited in the spread.

Whilst housing statements are required to be considered by Integration Authorities, better relationships could be built with the SFHA/Scottish Housing Regulator to raise awareness and understanding of how social work can work alongside housing professionals, and to influence housing associations nationally when they’re planning adaptations made to existing housing stock to allow for transitions from family life to house people with mobility issues, frailty and living alone as well as dementia. In addition, we should require housing developers to contribute toward the provision of community health and social services. We could require a certain proportion of houses to be ready for use by someone with a high level of support needs.

There should be a closer alignment of local authority housing services with health and social care partnerships to ensure that there is effective local housing planning to support population needs.

The Scottish Government has developed a draft vision for housing for 2040[17]. Whilst this document references a number of key challenges such as the ageing population, increasing health and social care needs, child poverty, homelessness and welfare reform, it does not go far enough to acknowledge some critical issues such as the housing needs of people with dementia, flexible care and support services for people who are older inclusive and intergenerational communities. Crucially, ‘places of care’ should not necessarily be envisaged as care homes. Consideration should be given to how we commission services that allow people to stay in their own homes and communities, supporting their relationships and identity, rather than moving people into residential settings.

Community spaces

We should focus on building sustainable communities. Statutory social work, social care and health services are not the answer in isolation.

Spaces in communities should be fit for the purpose of meeting the needs of more vulnerable adults. Whist soft play is ubiquitous for young children, we should have similar sensory spaces for other groups such as people with autism, or people who need a quiet communal space. Architecture and Design Scotland have conducted good work on age-friendly places[18] and on redesigning town centres to provide opportunities for more intergenerational and inclusive living.

Technology

Technology needs to be at the heart of the future of care preserving independence and supporting social inter-dependency. It should not substitute for human contact. The National Digital Platform[19] should incorporate as great a focus on technology to deliver social care as on health and should be given the highest priority as a core enabler.

Technology that allows people to monitor their own wellbeing and the use of algorithms to trigger service response when needed should be standard. It should deliver platforms to make it easier to find and refer to organisations that offer support. Technology Enhanced Care should not focus solely on established applications, like community alarms, tracking devices and sensors, but should include emerging uses such as apps and widgets on Smartphones, and the use of artificial intelligence virtual assistants, which are widely available.

IT to support Self-directed Support would include systems for booking care and short breaks, and how to make use of individual service funds.

Workforce

A key driver of any adaptive system change is workforce; selection, training and coaching. In order to attract a competent and committed workforce, remuneration should reflect the complexity and responsibility of roles across a varied employment landscape. Innovation is required in how we support people to employ their own personal assistants (employed with an Option 1 Direct Payment). We need an inward migration system that can attract skilled workers into the social care field, and note with dismay the likelihood of too high salary thresholds for European immigrants post-Brexit.

We need to focus on attracting workers to urban, rural and island areas and keeping them engaged and motivated. We require a gendered analysis of the workforce if we are to understand how to attract men into the social care workforce and how to best support women in the workforce.

An integrated workforce must be drawn from across disciplines and be multi-skilled across both health and social care. This will require developments in foundational training and changes in workforce regulation.

With budget cuts over the past decade, local authority social work learning and development teams have all but disappeared, impacting greatly on the ongoing training of social work and social care staff. Staff, on the whole, make do with what they source themselves on an ad hoc basis, and it is limited if any dedicated time-to-learn. This highlights the lack of parity of social work and social care with other professions such as teaching and nursing. If adaptive change is to be implemented effectively, then the workforce requires not only high standard skill-based training but ongoing intensive coaching and supervision, and to expect pay rises in line with those offered to nurses and teachers.

- What needs to happen to ensure the equitable provision of social care across the country?

The fundamental driver of equity is to ensure that investment in social work and social care is sufficient to meet population needs and choices from early help through to crisis intervention. For too long we have heard the rhetoric of ‘record investment in the NHS’ compared to ‘the soaring cost of social care. We need to reconsider the value of social work and social care and promote public awareness of the interrelationship, and the crucial role that social work and social care play in supporting our communities.

Social Work Scotland is supportive of the development of national practice models which support consistency of approach across Scotland whilst allowing for variation anywhere this is reasonable in the context of local geography, demography and cost of living. We believe that there are opportunities that need to be seized within the current reviews of Integration and Adult Social Care to reimagine partnerships within the local and national government, social work and health (including Public Health Scotland) and across community planning.

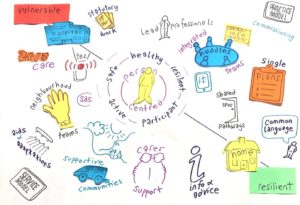

Our Adult Social Care Standing Committee is looking at the development of a common practice model for adults similar to the national practice model for children (Getting It Right For Every Child) based on work already undertaken by Highland Council (Figure 1) and by Dundee HSCP.

Figure 1.

Having a common practice framework across integration authorities would support a coherent performance framework for social work and social care service delivery and for integration across social work, social care and health, and would orientate the systemic adaptive change necessary to embed the progressive policies of personalisation and integration.

The benefits include a common shared language and shared pathways, with single integrated health and care plans for people. A common practice framework would help align data and IT systems across councils and health. Integrated teams have been supplanted on top of pre-existing professional teams in some areas, so there is duplication. However, there is a need to test out new ways of doing things safely, while protecting current systems, however imperfect, and this requires implementation funding.

Taking a similar approach, Social Work Scotland is developing a national framework for Self-directed Support as the key deliverable of the SDS project. This will take cognisance of the person’s life journey and the service systems required to support personalisation.

As noted on p8, Social Work Scotland holds that the existing eligibility criteria should be reviewed. Current eligibility criteria are deficit-based assessment of levels of risk to an individual if care is not provided. They run contrary to the principles of personalisation, as they drive time-and-task service provision. They are applied differently across Scotland and result in unnecessary variation in outcomes for individuals. There should be consideration given also to the variation in charging and contributions policies across local authority areas and their disproportionate impact on individuals with similar needs in different areas of Scotland.

Currently the rules of ‘Ordinary Residence’ mean that people receiving care at home who move across local authority boundaries are subject to reassessment under different (and non-transparent) local policies and systems, and can see their care provision significantly altered as a result. This has become particularly obvious in our prison work as people’s rights to ask the Parole Board for release are impacted by disputes round ordinary residence and what appears to be reluctance to fund care packages and accommodation for people with more complex needs. We would like to see a rights-based review of ‘Ordinary Residence’ undertaken with the aim of improving portability of care across local boundaries as well as the processes around transitions between settings.

For further information, please do not hesitate to contact:

Dr Jane Kellock

Head of Strategy, Social Work Scotland

jane.kellock@socialworkscotland.org