13th January 2021

Social Work Scotland is the professional body for social work leaders in Scotland. The Scottish Association of Social Work (SASW) is part of the British Association of Social Workers, an independent membership body for social workers across the UK. Both organisations work closely with partners to shape policy and practice and improve the quality and experience of social services. We are responding to this inquiry together, bringing together the views of frontline social workers and managers who are employed in the public, private and voluntary sectors, as well as those operating as independent practitioners. Our joint membership is diverse and is located across all parts of Scotland, experiences throughout the pandemic have been highly variable, in line with the differences in decisions and approaches taken by local areas. We profile in this submission here the common themes to emerge from their feedback over the past ten months.

Keypoints

- While acknowledging that COVID-19 has manifested some new equality and human rights issues, overwhelmingly its impact has been to exacerbate existing inequalities and lay bare the fragility of the systems (services, people) who protect and give meaning to human rights. This is particularly the case for those individuals whose rights were more vulnerable prior to the pandemic, due to age, disability, gender, sexuality, socio-economic status, race and ethnicity, housing security, mental health, etc. Well-resourced public services (such as social work and social care), as well as an active civic society (including charities, voluntary organisations, etc), are essential to the realisation of Scotland’s vision of a rights-based, equal society. Instead, the funding of the social care system has fallen in real terms over the decade of austerity – in the opposite direction to increasing need due to demographic and other changes.

- The many different dimensions of social inequalities create overlapping layers of disadvantage, which are multiple for many people; these have been tracked by the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic. In managing our ongoing response to COVID-19, and in our “rebuilding better” after, careful attention must be paid to the views and needs of these specific groups, ensuring plans take account of their vulnerability to the virus itself and/or its wider socio-economic and mental health effects, and deal with root causes.

- Social work is a critical component in many public service systems. In children, adult and justice services, social workers mediate access to a wide range of support (e.g., child and adult social care), deliver specific interventions and protect the interests of those unable to do so independently. COVID-19 has restricted social work’s ability to perform these functions, due to staff absence, work-from-home restrictions, limited PPE (in the early stages of the pandemic) and prioritisation of other urgent issues. As a result of social work being less present and accessible, the rights of some individuals will have been affected. Social workers, with colleagues across social services, have worked tirelessly to minimise this impact, but there are limits to what can be achieved through remote working or with depleted teams. Vaccination holds out the promise of a return to face-to-face interaction and relational work on a much wider scale than is currently possible. However, the impact of COVID-19 on the profession, and the organisations which employ them, is likely to stretch over a number of years. Any plan to re-address the inequities and rights impact of the pandemic must have within it a commitment to address issues impeding the delivery of effective social work practice.

- The pandemic has revealed the limitations of a ‘rights bearer’ and ‘duty holder’ framing of human rights. Corporate bodies, such as local authorities, may hold duties to uphold rights, but those corporate bodies are in reality just organised groups of people, all with their own needs, vulnerabilities and rights. The response to COVID-19 has, universally, forced employers to consider the welfare of their staff and the urgency and risk of the work they are involved in. Within the NHS, that has led to the cancellation of operations and delayed treatment for thousands of people. For social work and social care, it has meant, in some cases, reductions in the level of support that can be made available. A realistic appraisal of the impact of the pandemic on rights and equality should highlight the responsibilities of employers to keep their people safe, and the enormous challenges they faced in the early stages, seeking to secure solutions that would enable professionals and others (such as social workers, social care staff and carers) to resume their work.

- Just as people rely on other people to give meaning to their human rights, the rights of different individuals can sometimes be in tension, or even conflict, with each other. In some cases, an individual’s exercise of their right to put themselves and/or others into potential harm. It is the unique role of social work to assess an individual’s needs, understand their wishes, and promote their interests and wellbeing within the framework of their human rights and the current service/resource context. Sometimes this involves making decisions in an individual’s interests that are at odds with their (or a family or friend’s) wishes. Such situations demand a high degree of sensitivity and skill to manage, and are, by their nature, often contentious and emotive. We make this point to underline the importance of taking a broad and nuanced perspective in any evaluation of how human rights have been impacted in the pandemic. Every individual’s story is complex and multifaceted, and understanding comes from a breadth of perspectives.

- The virus, its impact on people’s health, and the impact of measures we have taken to contain its spread have most affected least advantaged in our society (on all dimensions: income and wealth, housing, digital, social, etc). 2020 and 2021 will have served to exacerbate our existing inequalities. Our hope is that, in having these inequalities more clearly surfaced, and a wider proportion of the population made aware, through their own experiences, of the challenges brought about by low incomes, isolation and family stress bring, the public’s appetite for addressing the underlying structural factors will be strengthened.

Question1: How have groups of people been affected by the virus?

In assessing COVID-19’s impact on equalities and human rights it is helpful to distinguish between the effects related to (a) the virus and disease itself[1], and (b) the actions taken by public authorities to contain the spread of the virus and protect vulnerable groups, access to emergency services, etc. Social workers have been involved throughout the pandemic in mitigating the impacts seen in both domains (albeit the majority of our activity has focused on the issues created by state efforts to contain the virus, which have affected every member of society in some way).

(A) Impact of the disease

As has now been well documented, the disease COVID-19 does discriminate. It has, to date at least, disproportionately affected older people, those with underlying health conditions, members of our Black, Asian, and other Minority Ethnic communities, and people with low incomes or precarious employment (e.g., zero-hour contracts). The reasons for this prejudice are various, including, in these groups, higher than average numbers of people living together under the same roof (be it a care home or family home), exposure to the virus through public-facing roles (e.g., public transport workers, nurses and healthcare assistants, etc.) and above-average rates of pre-existing co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes, obesity, hypertension). These factors coalesce together into an increased risk of catching the virus, and then an increased risk of the virus manifesting a serious or fatal response.

The impact of these increased risks has manifested in many ways, with individuals and families affected by some or all of the following:

Stress and anxiety

- Worry for self and family, about illness and/or social and financial impacts

- Worry about the transmission of the virus to loved ones, known contacts, professionals and carers, colleagues, other residents in-home or accommodation, unknown members of the public, etc.

- Worry about putting pressure on the health service, reducing its capacity for others.

Loss of income

- Actual reductions in income because of not being able to work

Loneliness (reduced human contact and self-isolation)

- Reduced in person contact with family, carers and professionals.

Recovered but with “long covid”

- Development of chronic health conditions, impacting on long-term ability to work, participate in education, society, etc.

Time in hospital

- Range of experiences including near-death and trauma, as well as the joy of survival

- Consumption of scarce resources including deferment of services required by people with other medical conditions leading to ‘survivor guilt’.

The decline in mental health

- Various psychological impacts, exacerbating existing conditions and provoking new ones.

Death

- Loss of future lives

- Bereavements and long-term loss to loved ones, families, friends

- Financial loss to families and wider society (multipliers, taxation, etc)

- Loss of contributions to society, and local communities

This is not an exhaustive list, but it illustrates that, for those who have caught the virus the potential impact on their human rights cannot be more serious, with loss of mental and physical health, work, and even life. And with the knowledge that the COVID-19 virus does not affect all groups in society equally, but that all groups are interconnected, it is understandable that governments around the world have taken such drastic all-of-society action in their efforts to contain it.

(B) Efforts to contain the virus

The public health measures introduced to slow the spread of the virus only have historical comparators in wartime. Every aspect of life and every individual, family and community has been affected. The scale and severity of restrictions (on the economy, social contact, movement, etc.) has meant that the virus, directly or indirectly, has impacted the rights and wellbeing of every person in the UK. But as with the discriminate impact of the virus, affecting some groups more than others, the impact of efforts to contain it have not fallen evenly on society. As social work practitioners and managers we have had a front-line perspective on this throughout the pandemic; particularly in respect to people who are vulnerable or need additional support, for whom we provide or coordinate services. This includes children, families, parents, carers, adults with disabilities, older people and people involved in the criminal justice system.

Among the many impacts of restrictions over the past year, of particular note in respect of this inquiry are:

Increased levels of poverty

- Poverty, much of which existed prior to the pandemic, is a key underlying factor for the escalation of the crisis in many households[2].

- Financial pressures resulting from insecure or total loss of employment and/or insufficient government support (for example where individuals must self-isolate) has contributed significantly to financial insecurity. The Government’s commitment to free school meals and increased levels of financial support have ameliorated this to some extent, but the medium to the long-term impact of increased anxiety within families (and to individuals within those families) may be serious.

- Increase in food poverty (with its concomitant impact on education, health, etc.).[3]

- Increases in applications for welfare and crisis support[4]. Accordingly, social work has faced increased demand for practical support around income maximisation and housing.

Digital poverty / inequality

- Some individuals/families have been able to continue to participate effectively in school, healthcare, routine assessment, etc. thanks to digital connectivity. Indeed for some people, the move of many services online has been beneficial, removing the need and cost of travel, etc., and changing the terms of their interaction with professionals. However, for others, the move online has meant marginalisation and the loss of support/service. The pre-existing ‘digital divide’ – reflecting inequality of access to knowledge, hardware, software, data and support – has been exaggerated, with those most likely to lose out being those already most disadvantaged. Digital connectivity is no longer a “nice to have” when essential services move online.

- The move online has also encouraged new types of financial fraud, increased exposure to online sexual grooming and the potential for other forms of exploitation of vulnerable people[5].

Disruption to referral routes for social work and social care

- Because engagement with schools, GPs, hospitals, etc. has significantly reduced, along with home visits by nurses, voluntary organisations, etc., referrals to social work or police for vulnerable children and adults have been disrupted, leading to delays in issues being identified. Early notification of concern is critical to prevent situations from deteriorating further, leading to more serious problems.

Disruption to social work, social care and community services

- Social work and social care services entered the pandemic with insufficient capacity to meet demand related to population ageing, widening inequalities and growing social care needs[6]. As the pandemic took hold, sickness, self-isolation and re-deployment reduced capacity further. Limitations on PPE, national guidance on home visiting and other factors also impacted social work’s ability to reach people vulnerable or in need.

- Voluntary sector and community organisations/services forced to close (e.g. day services, etc.), restricting the opportunities available to certain groups, such as those with disabilities, to leave their homes, maintain relationships, etc.

- Public sector and independent (voluntary or private sector) providers of care and support are forced to reduce the care packages they can service.

Increased isolation and loneliness, impacting on mental health and wellbeing

- Isolation and loneliness have increased across all sections of the population, with a significant impact on mental wellbeing and mental health. However, for individuals and families who were already isolated (as too many older people, adults with disabilities and parents were) the closing of services and reduction of interaction/visits from family, carers, support workers, etc. has exaggerated this further.

Increased pressure within families

- Poverty (be it financial, food, digital, housing) creates stress within families. The government’s efforts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic have increased those pressures within many families.

- Further pressure has been built through individuals spending extended periods of time exclusively together at home, the demands of homeschooling, disruption to exams, young people’s lack of access to friends, the general social anxiety about the future, etc.

As with the impacts of the virus itself, this list is far from exhaustive. What we have tried to illustrate is that the restrictions imposed have surfaced the significant inequalities which existed in society before the pandemic. And, moreover, the fulfilment of people’s human rights relies on a broad base of civic and public services being accessible. This is particularly true for people and families with fewer socioeconomic advantages. Remove the scaffolding from around individuals and communities, and the structure is less resilient to major external and internal stresses.

Q2: Which groups have been disproportionately affected by the virus and the response to it?

- Children and Families:

Children, as a cohort, have been particularly affected because of the disruption to education (from early learning and childcare through all stages of school) and the dramatic reduction in opportunities for play, peer and extended family interaction, creativity, learning, travel, etc. These opportunities, complementing formal learning, shape the adults we become. The absence of school and another child/youth activities has also significantly reduced the chance to identify issues early and offer help. That is particularly problematic for young people’s mental and physical health. The long-term legacy of these COVID-19 months is yet to be seen, but it is children and young people whose lives will be most shaped by it. The world of employment will be changed (possibly with fewer of the sort of jobs young people begin with), and public debt built up to underwrite the government’s response will shape the public and political debate for decades to come. At an individual level, disruption to schooling and issues with mental health may determine many future choices.

Within the cohort of ‘all children, specific groups have been affected more than others. For example, those affected by domestic abuse. Levels of domestic abuse in Scotland have been a persistent concern for social work, charities and policymakers for many years, but on the basis of calls to third sector helplines, the pandemic has led to increased prevalence. This is consistent with what we know about domestic abuse and its relationship to wider stressors within the family. With services reduced or closed, and people encouraged to isolate as much as possible, we have reduced our collective ability to spot and respond to cases at the early stages. This has limited our capacity to protect the rights of children (and others impacted by abuse within the household). Our experience suggests that much greater support is needed for non-abusing parents and children and that we must engage much more effectively and assiduously with perpetrators. Many local authorities and organisations were building this strengths-based approach (such as the internationally recognised Safe and Together™[7]) at the start of the pandemic, but unfortunately, work in some areas has had to be delayed to accommodate other priorities.

The true extent of child sexual abuse and child criminal exploitation through the pandemic has been hard to gauge[8], but we expect it to have increased. Third sector colleagues and the police draw attention to the significance of the interaction between technology-assisted and direct contact abuse, and with the move of children’s lives online, the increased risks. The pandemic has underlined the need for a closer examination of the context of abuse outside the family, and a consideration of how to intervene in both physical locations and online platforms (a theme explored in a recent Social Work Scotland hosted seminar[9]). More generally, ensuring child protection during COVID-19 has been challenging, with the everyday monitoring provided by schools and other universal services reduced or removed. Social work professionals themselves have been restricted in their ability to interact with families, with reductions in-home visits, supervised contact, etc. Colleagues report concerns about patterns of Forced Marriage, Female Genital Mutilation and Honour Based Abuse.

There has also been a disproportionate impact for children involved in the Children’s Hearings System and courts. Permanence decisions have been delayed, existing Orders have been rolled forward without an expiry date (meaning that families risk being subject to state intervention longer than necessary), and only priority cases have been heard by Children’s Hearing panels, potentially limiting access to services from social workers and others. Figures provided to the Scottish Government (as part of the monitoring of COVID-19’s impact) indicate that since March 2020 there has been a significant reduction in the number of children becoming looked after away from home.[10] At this stage, there is not enough data and intelligence to confirm whether this is a result of system changes or limited access to resources and not necessarily because of reduced need or better practice. This needs to be explored to ensure that children’s rights are not at risk from inaction.

The challenge of promoting the relationships and wellbeing of children looked after away from home has been accentuated by COVID-19. Social Work Scotland has been central to the development of a framework for decision making about contact[11], assisting practitioners to make extremely difficult decisions. For example, there have been significant challenges around contact, for example between children and birth parents, balancing the benefits with risks, such as spreading the virus to foster or kinship carers (often an older population) or between different parts of the country (which may have different rates of infection and restrictions in place). The limited number of safe physical environments for indoor contact has further restricted options.

Social workers have consistently reported how stretched and affected many kinship and foster carers, and the children in their care, have been, with individuals feeling isolated and disconnected from their normal networks (formal and informal) of support. Local areas have done creative work using virtual support and new models of practical, material help, but for many of these families, it has remained a very difficult year. We take heart from the adaptation and resilience the families have shown, and the positive stories emerging of, for instance, effective family group decision making taking place which has kept children out of the care system.[12]

Families with children who have complex physical or learning needs have been particularly impacted by the closure of educational settings, having to assume 24-hour responsibility for care and education. There are specific risks for these families in terms of isolation and burnout without frequent opportunities for support and respite. And for those at or near school leaving age, the crucial transition planning for people with additional support needs (enabling them to make successful moves into further and higher education, or employment) has been disrupted, opportunities restricted.

(B) Adults

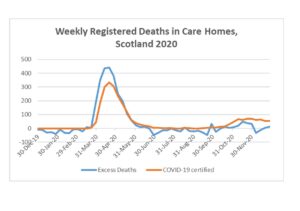

Adults living in care homes, whether older people or adults with complex needs, have been disproportionately affected by the virus and the response. In the first phase of the pandemic, there were high levels of excess deaths (compared to the weekly 5-year averages for 2015-19, not all of which were recognised on death certificates as COVID-19 related during the period before testing became more widely available[13].

Some social care workers in residential homes, and also in the community, have also died as a result of contracting COVID-19 through their work, as sadly has been the case for other groups of essential workers.

From a social work perspective, it became increasingly important to ensure that people’s human rights and mental health were being considered alongside (rather than secondary to) clinical excellence and infection control. Issues as varied as discharges from hospitals to care homes, restrictions on visits, limited interaction within homes, mass testing, use of Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation forms[14], have all presented complex and nuanced decision making. And they have proved highly problematic for many care homes, especially those supporting people with cognitive needs. The enhanced oversight of care homes duty, placed on Chief Social Work Officers and other professional leaders, was an attempt to ensure a balanced assessment of risks, rights and needs in shaping local strategies. As we write, the vaccination programme is being rolled out through care homes, and we hope this will enable residents to access their rights to see family and friends and to ensure they get the full range of services and support they need.

At the core of the social work role is public protection; assessing risks and benefits in an ecological model, with the aim of securing the best outcomes for an individual, with their needs and wishes met and interests protected. In some instances, social workers are empowered to take actions to protect the interests of an individual, possibly bringing them into conflict with the individual or their carer/family, who wish to take a different course of action. This is a difficult but essential role in a society where not all individuals, whether due to incapacity or circumstances, are in a position to determine their best interests alone. And while families have an undisputed right to inform and lead decision-making in such instances, it is the case that they do not always have access to all the information, or necessarily have the rights, needs and interests of the individual as their primary concern. Over the course of the pandemic, the social work profession’s ability to perform this role has been restricted, leading to concerns about the welfare of such as adults with incapacity. Due to reduced reporting channels (fewer agencies and primary care contact with people and families at risk of crisis) and restrictions on movement and interaction, it has been difficult in some cases to ensure the rights and welfare of some individuals are being maintained.

Early intervention and community supports are critical to maintaining good mental wellbeing and mental health. Where these are not available, we can expect to see more people reaching mental health crises. This is likely to be compounded where the economic situation is worsened. With people’s mental health needs going unmet, detention – a deprivation of an individual’s liberty – is being considered more frequently than we, as a professional group involved in such decisions, would like to see it. As officers of local authorities within partnership arrangements, Mental Health Officers (specialist social workers with additional qualifications in mental health) are not sufficiently empowered to ensure provision meets the assessed needs. To ensure the rights of individuals with mental health issues are upheld, MHOs (and other relevant professionals) need access to specialist and community resources, over which people are offered choice and control. We believe that decisions regarding detention should be made after a face-to-face assessment of patients, but we are aware that due to staffing constraints, this is not always the case. Whilst the number[15] of people being detained due to their mental health has risen during the pandemic, this is in line with year on year rises. There is evidence, however, from the Mental Welfare Commission that some of the safeguards around detention have been used less frequently than previously. We are concerned about the critical shortage of both MHOs and “Section 22” medical professionals. We note that the Tayside Independent Review report “Trust and Respect” was explicit in finding that a shortage of Registered Medical Officers impacted detrimentally on the patient’s journey.

People who are homeless initially benefitted from the programme to ensure that everyone was off the streets, and the route map for “Everyone Home”[16] has been developed to make asking about homelessness an expectation across public services. However, in order for this success to stand beyond the pandemic, public services must continue to be resourced appropriately to attend to the multiple underlying structural causes of homelessness (including additions, mental health, debt, etc.). Otherwise, we risk returning to pre-pandemic levels of homelessness (or higher, considering the precarious financial situation many people face), with the additional challenge of a diminished voluntary sector, its finances limited after a year of reduced income.

(C) Adults involved in the justice system

Justice Social Work delivers reports to Scottish Courts, provides or commissions community-based programmes as an alternative to prison, and is responsible for a range of expert risk assessment support to the police, prison service and Parole Board. Requirements for physical distancing, and the universal impact on staffing through sickness, isolation and redeployment, have reduced the ability of justice social workers to deliver group programmes and coordinate unpaid work activity. This has a very significant impact, in terms of rights and equalities, on the individuals subject to relevant courts orders, effectively extending sentences and prolonging involvement with the justice system.

Both Social Work Scotland and SASW[17] have articulated concerns to the Scottish Government around the backlog of community order ‘unpaid work’ hours[18]. We believe that without a systematic reduction in the number of outstanding unpaid work hours (through revocation or variation of orders) there is a major risk that Justice Social Work (JSW) will be overwhelmed, with serious consequences for the wider justice system and the rights of both social work professionals and individuals and families, and victims. Whilst some funding has been made available to buy in support from the Third Sector, this will not release the number of hours necessary to meet the backlog in demand.

Before the Coronavirus pandemic, there was an increasing focus on expanding early intervention measures such as Diversion from Prosecution and Structured Deferred Sentences which help individuals to avoid unnecessary contact with the criminal justice system and deliver swift interventions which can interrupt a cycle of offending. Many of the strategies now in place to deal with the backlog within the justice system require heavy input from CJSW, but simultaneously the capacity of CJSW has reduced[19].

People in prison have experienced significant additional curtailments to their rights as visits, time out of the cell, meaningful daily activity and access to fresh air have all been reduced. The number of people on remand has increased as has the length of time people are remanded impacting people’s lives, housing, work finances and relationships. Children who have a parent or sibling in prison will experience the removal of the person from their lives in a more extreme way than even prior to the pandemic.

Q.3: Is there specific equality or human rights impacts on groups of people as a response to the virus?

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) recently published a report on changes to social care provision during COVID-19 and its impact on human rights[20]. It details the experiences of individuals receiving health and social care support, with a focus on the rights of persons with disabilities, older people, carers and children. The testimony of many of those who participated in the research is distressing, highlighting the serious consequences for individuals when support cannot be accessed.

The context around these experiences were the efforts of NHS, local authorities and independent care providers (working together as Health and Social Care Partnerships) to ensure support was available to meet all assessed (and anticipated) needs, within safe staffing levels. Plans took into account high rates of staff absence, due to sickness and isolation. The restrictions, and necessary steps to protect staff, meant that many social workers and social care staff would be limited in their ability to work. The focus was on protecting critical services for those most in need. However, the timeframe for how long this would be needed was not clear at the outset, and the working assumption was that measures to reduce care packages for some (to ensure some access for all) would be required for weeks, not months. It is clear now that the impact of these measures varied across Scotland, reflecting different levels and types of pre-pandemic service provision and workforce demographics. But in all areas of Scotland those requiring social care support, and those caring for them, have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic because of the limits the reductions of support place on an individual’s independence (beyond the national restrictions everyone has had to adapt to).

Because many face-to-face support services such as day centres and support groups had their operations significantly reduced as a result of public health requirements, the pressure of continually caring for people during the crisis will also have had an effect on the wellbeing of carers. Carers who support their family members or friends to live independently have experienced isolation and reduced support, with many increasing their caring hours to protect the supported person from additional footfall into their homes and related risks of exposure to the virus.

The SHRC report calls for the social care system to be reimagined as a dynamic interplay within a social infrastructure that supports citizens’ human rights as individuals within families and communities. SASW and Social Work Scotland agree strongly with this vision, but take this opportunity to emphasise that it is only possible when the system is populated by sufficient numbers of skilled people, committed and enabled to deliver the best outcomes for individuals. Such a system, requiring a significantly larger ‘workforce’, is not possible within current funding levels. A return to pre-COVID-19 structures and mechanisms of support, even if funding were increased, would not address the issues flagged by the SHRC report.

It is likely that one of the effects of the pandemic will be to increase the number of people needing health and social work and social care support as a result of:

- The immediate impact of illness, loss and grief and trauma

- The economic impact may mean more individuals and families experience derivation and poverty which is a key factor in bringing people to social services

- The longer-term impact of long-covid, the reduction in planned health treatment and the need for physical distancing reducing opportunities for preventative and early intervention means that more people will have higher levels of chronic physical, mental health and social needs.

We take heart from examples highlighted in the Care Inspectorate’s report, ‘Delivering care at home and housing support services during the COVID-19 pandemic’[21], where local partnerships successfully adapted and flexed their support to meet people’s needs during the pandemic. Teams in local government and the voluntary and private sectors have innovated and adjusted to put people’s needs before contractual hours. The capacity for change and positive reform is in place, and we look forward to the upcoming discussions about how to realise that, in response to the Independent Review of Adult Social Care.

Q.4: What do the Scottish Government and public authorities (e.g. local authorities, health boards etc.) need to change or improve: as a matter of urgency & in the medium to long term?

This question frames a critical debate in an unhelpful way. Locating responsibility for change and improvement solely with the Scottish Government and public authorities not only presumes that they have the capacity/resources to effect changes, but it also encourages us all to see the problem as ‘theirs’ to resolve. The issues we have profiled in this response, such as poverty, structural inequalities and the public-civic infrastructure which give effect to people’s human rights, can only be addressed through both political and societal action. As with climate change, or changes to consumption that limit our impact on biodiversity, public authorities of all kinds are key players. But in democracies like Scotland, they move and act within a space we, the public, give them. Calling for public authorities to effect changes that will require significantly more resources, without our clearly accepting the need to provide those resources (through taxes, government borrowing or reallocation of existing spend), will simply perpetuate the public policy debates we have had for the past ten to fifteen years.

The funding of social care

Social Work Scotland and SASW are particularly concerned about the impacts of the deepening financial crisis in social care, which we have highlighted recently in our respective submissions to the Independent Review of Adult Social Care (IRASC). The crisis also exists in children and families social work services, and criminal justice social work, which are not within the scope of the Independent Review of Adult Social Care.

Adult social care spending per head in Scotland has fallen dramatically for Scotland’s older people, less so in England but more than it has in Wales (see graph in download here).

Spending per head on adults aged 18-64 – mainly people with learning disabilities or physical disabilities, or in need of mental health support — has fared better, but in Scotland is back to the 2010-11 levels whilst the numbers of people living with disabilities, or with mental health problems, have both increased in Scotland, as in the rest of the UK. (The figures in the graph come from the Treasury’s Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2020).

Social Work Scotland’s submission to IRASC on Demographic Change and Adult Social Care Expenditure in Scotland[22]is mostly concerned with the Scottish Government’s own H&SC Medium Term Financial Framework (2018), which estimated the increased demands at 3.5% for adult social care as a whole, and 1% for the NHS.

We found that the estimated additional spend on 3.5% per year for adult social care is well supported by research in England by the London School of Economics using sophisticated modelling from survey data not available in Scotland. That also shows that the additional demand for services for younger adults with a learning or physical disability, due largely to improved longevity, is at similar annual percentage increases as demand from older people.

However, our analysis does not support the lower increases for the NHS in the H&SC Medium Term Financial Framework – these are 1% per year for demography, compared to estimates by the Institute for Fiscal Studies of 2.2% per year for England and the UK as a whole (in their major study Securing the future published earlier in 2018).

Our analysis also does not support the annual workforce increases set out in the Scottish Government’s Integrated Health and Social Care Workforce Plan for Scotland published in December 2010, which stated that:

The Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Framework (MTFF) estimates that to address the effects of demand, we will require 1.3% per annum more NHS employees and 1.7% per annum more social care employees in the period to 2023/24”.

Those figures cannot be found in the MTFF and, we believe, are incorrect. In any event, Scottish Government funding to councils for adult social care has not been increased to the level required to meet demography, let alone address the unmet need that has accumulated for survivors of the decade of austerity. Increased funding for social care needs to fully recognise the impacts of demographic change, in line with the Scottish Government’s own medium-term planning, and on a corrected basis for the NHS in Scotland.

The role and status of social work

Social work is one of the few ‘key worker’ professions that is, when able to operate as conceived, proactive and person-led. It exists (and in legislation is empowered) to take action in defence or support of people made vulnerable by their circumstances. Those we work with may be less likely to be heard and may struggle to stay afloat when the scaffolding of support is stripped away (as it has been during COVID-19). Social work sees people in their own individual context, recognising that an individual’s relationships, strengths, interests, etc. constitute the person, and that to give meaning to their human rights is to reinforce and promote those assets. But we must also balance individual rights with those of others, and consider the risks of certain actions to the individual themselves, their families and wider society. Our role must be to enable those people to have a voice, and to provide protective support or intervention where that becomes necessary.

As illustrated above, before COVID-19 social work (and the wider social care system it underpins) was already facing significant financial constraints; demand and aspiration were not matched by available budgets. The 2019/20 COSLA report Investing in Essential Services, highlighted the challenges local authorities face to meet the outcomes and targets identified in the national performance framework within existing resources, referencing specifically child poverty and vulnerable adults[23]. The strain that the social care system is under, and the conditions in which care professionals must practice, has been well documented in a range of reports from academics and institutions. The latest such report from the University of the West of Scotland (UWS) (Decent work in Scotland’s Care Homes) highlights a sector facing ‘systemic issues, a lack of respect and in need of cultural change’[24].

Within the current landscape, social work professionals – trained to respect and uphold human rights and work alongside individuals and communities (balancing and holding needs, risks and interests) – find themselves working in systems that can force them to be ‘assessors’ of risk and gatekeepers to over-rationed vices.[25] This not only means we fail to realise the human rights and outcomes potential of social work, but we slowly erode the enthusiasm and commitment of the professionals themselves.

While there has been positive innovation, acceleration of developments and much useful learning from the past year, the pandemic has made it harder to work alongside people and families at the challenging points and transitions in their lives. This has posed a unique challenge to social work, which is support based within and upon relationships. Feedback from our members has highlighted a number of further issues for the profession, limiting our ability to provide support and services and significantly affecting the working conditions and wellbeing of social workers. We would welcome any opportunity to discuss this further with the Committee.

Social Work Scotland’s Chief Social Work Officer (CSWO) committee has reported that the pandemic’s impact on the social work profession has been to compound pre-existing issues. These include dealing with real-term reductions in budgets (which in turn increases the workload on individuals), difficulties in recruitment, lacking visibility and authority in key decision-making forums, the disparity in social work and social care’s pay and conditions between health and social care partnerships. The split professional leadership across adults, justice and children and families is also seen, by some, to weaken oversight and coordination.

In July 2020 the Social Workers’ Union[26] reported that one-third of social workers are considering leaving the profession as a direct result of the pandemic. The union released an action plan calling for increased mental health support, a social work recruitment drive and a pledge not to re-introduce austerity measures post-pandemic.

As we move through and, hopefully, out of the pandemic, we would like to see and contribute to a re-imagining of the role and functions of public services. People are not simply ‘rights holders’ and professionals (such as social workers) are not simply ‘duty bearers’; we are all people, facing the challenges presented by the context, trying to deliver the optimum outcomes for individual and society, while having to balance competing interests, rights, demands and priorities. Similarly, public services must embrace greater creativity in how they support people to give meaning to their human rights and find genuine wellbeing. That will require a workforce who feel equipped and empowered to do what they were trained to do. The Human Rights Taskforce due to report in March 2021 will, no doubt, be considering a range of ways that public services and others can achieve this, and the Independent Review of Adult Social Care and The Promise are re-imagining support services for key groups.

For further information, please do not hesitate to contact:

Flora Aldridge Social Work Scotland

Flora.aldridge@socialworkscotland.org

Emily Galloway SASW

Appendix

[1] See World Health Organisation website: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it

[2] https://www.basw.co.uk/media/news/2020/oct/port-storm-poverty-aware-social-work-pandemic

[3] https://www.trusselltrust.org/2020/09/14/new-report-reveals-how-coronavirus-has-affected-food-bank-use/

[4]https://scotland.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/1934099/Shelter_Scotland_briefing_LGCC_Homelessness_and_Covid_140820.pdf/_nocache

[6] See Social Work Scotland supplementary submissions to the Independent Review of Adult Social Care: https://socialworkscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SWS-Supp-Sub-1-DEMOGRAPHIC-CHANGE-AND-ADULT-SOCIAL-CARE-EXPENDITURE-IN-SCOTLAND.pdf; and https://socialworkscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SWS-Supp-Sub-2-ASC-EXPENDITURE-IN-THE-DECADE-OF-AUSTERITY.pdf.

[7] ABOUT THE MODEL – Safe & Together Institute (safeandtogetherinstitute.com)

[8] https://www.scra.gov.uk/2020/10/sexual-exploitation-of-children-new-research-report/

[9] https://socialworkscotland.org/contextual-safeguarding-event-2020/

[10] Coronavirus (COVID-19): children, young people and families – evidence and intelligence reports (various)

[11] https://socialworkscotland.org/publication/connections-for-wellbeing/

[12] The IRISS summary of a University of Edinburgh/City of Edinburgh Knowledge exchange project illustrates the value of this rights based approach in the most urgent of circumstances https://www.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/recognition_matters_briefing_june_2020.pdf

[13] National Records of Scotland: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/weekly-and-monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths/deaths-involving-coronavirus-covid-19-in-scotland (Week 53)

[14] OLDER PEOPLE BEING PRESSURISED INTO SIGNING DO NOT ATTEMPT CPR FORMS – JOINT STATEMENT FROM AGE SECTOR ORGANISATIONS | Media | Age UK

[15] Detentions for mental health care during the pandemic – new report | Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (mwcscot.org.uk)

[16] route-map-4.pdf (everyonehome.scot)

[17] Letter for Humza Yousaf, MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Justice from SASW | www.basw.co.uk

[18] https://socialworkscotland.org/briefings/reducing-the-backlog-of-unpaid-work-hours-coronavirus-scotland-act-2020/

[19] https://socialworkscotland.org/consultations/pre-budget-scrutiny-2021-2022/

[20] https://www.scottishhumanrights.com/media/2102/covid-19-social-care-monitoring-report-vfinal.pdf, Chapter 3, page 15

[21] https://hub.careinspectorate.com/media/4171/delivering-cah-and-hss-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf

[22] https://socialworkscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SWS-Supp-Sub-1-DEMOGRAPHIC-CHANGE-AND-ADULT-SOCIAL-CARE-EXPENDITURE-IN-SCOTLAND.pdf

[23] https://www.cosla.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/14808/cosla-investinessentialservices.pdf

[24] https://dwsc-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Decent-Work-in-Scottish-Care-Homes-Report-Final.pdf

[25] https://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/publications/DC20011129CCD8single.pdf

[26] SWU: Social Work’s Six-Point Urgent Action Plan | www.basw.co.uk